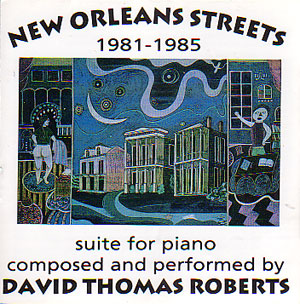

New Orleans Streets

(Solo Art Records, New Orleans, LA, 1992 - CD)

Status: Available at JazzByMail

Track Listing

- Introduction

- Decatur Street

- Burgundy Street

- Franklin Avenue

- Jackson Avenue

- Waltz

- Napoleon Avenue

- Magazine Street

- Toulouse Street

- Annunciation Street

- Broad Avenue

- Interlude

- Fontainebleau Drive

- Revenge

- Farewell

Liner Notes

When I premiered New Orleans Streets on September 20, 1985, at Dixon Hall at Tulane University, New Orleans, I provided the following remarks among the program notes:

New Orleans Streets is a fifteen-sectioned suite for piano. Featuring elements of ragtime, Latin American music, early jazz, Romantic piano music, rhythm and blues/early rock 'n' roll, hymnology, country material and music associated with the Mediterranean, it is a summary of the musical informants having the greatest impact upon my early life. Consisting of ten street-sections and five miscellaneous sections, the suite is obliquely narrative.

These literal guidelines encourage only the most pale expectations of what will follow. The darkness established by "Introduction" is soon discovered to be the rule of this world. The remarks also indicate nothing of what makes the suite a challenge for its composer to discuss. I have had to ask myself this: How revealing for my own psychic good should be an introduction to a work so charged with contorted autobiographical and social allusions? I am satisfied that, for those fluent in the musical idioms informing the work, all that must be evident is evident. Still, the temptation to share is compelling...

The listener who is conversant with the varieties of ragtime, New Orleans jazz (particularly Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton) and with early New Orleans rhythm and blues in addition to Romantic music has an immeasurable advantage in approaching New Orleans Streets. Indeed, those intimate only with European art music practices will be at a decisive loss here. For instance, the following phrase from "Farewell" may be readily understood as a variation of a Morton melodic trademark:

However, if one is uninformed of Morton, the "Chopinesque" character of the passage (an equally intentional reference in the florid repeat) will dominate the perception. While the references to New Orleans music and American culture are pervasive, none can be reasonably regarded as esoteric or private.

Formally, the origins of New Orleans Streets owe something to Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, the large Schumann piano works, Albeniz's Iberia, and German song cycles. Though the suite's ultimate impact is in complete performance, the sections can also be programmed in isolation. Many of my concerts feature three, four or five sections. In Oslo, February, 1988, I chose to include "Magazine" only, surrounded by ragtime compositions and pieces by Morton and Ernesto Nazareth.

Room for limited improvisation is built into the work, usually handled as a choice of combining ossias rather than freewheeling invention. But parts of "Toulouse Street," "Interlude," and "Farewell" call for such extemporizations and vary greatly with every performance.

I doubt that many listeners in the Western world can hear New Orleans Streets without registering its negativity. The suite that emerged from "Revenge" grew from phrases of private wrath into a piano novel preoccupied with collective despair and horror. Who can question any longer that U.S. cities have become bona fide hell zones? Does anyone yet pretend that they are not international symbols of all that is hideous? While Streets is fed by a panorama of conflicting New Orleans experience, it is clear that the work's dominant spirit is most explicitly voiced in "Magazine" and "Annunciation."

In accord with self-definition dating from childhood I have refused to tolerate the archaic sexual scripts of man as aggressor-seducer and woman as receptor-rejecter of advances. I not only disdain and lament the survival of this condition; I despise those who happily perpetuate it. Of the many ways in which this culture discourages sincerity and sexual dignity, the double denigration implicit in these roles has contributed most to my bitterness. It was on a night of the most concentrated rage at another example of this schemata that I conceived the beginning of "Revenge." Thus, as I paced the Carrollton area, the idea of a suite of streets unfolded.

My first evocation of New Orleans architecture was The Lower Garden District (1979-80). This dark tango is a direct ancestor of much of Streets and is virtually the musical equal of "Magazine."

It is the architecture above all that makes New Orleans a vital organism I carry everywhere. Though I point most readily to the now pathetic Greek Revival houses of the Lower Garden District when describing my relationship with the city, most of the older sections are at least as precious to me. Faubourg Marigny, much of Uptown, the French Quarter, Downtown and the best of the American Sector have also furnished the urban centerpieces of my consciousness.

It would be difficult for me to review New Orleans without the images being shaded somehow by the music of Ferd Morton. The Morton element is clear enough in "Introduction," and is soon reinforced by the opening of the coda of "Decatur," in which the classic Morton figure quoted in "Farewell" is given a Mediterranean twist. Morton's presence is felt throughout the suite, recalling his centrifugal place in the regional-nationalistic branch of my musical life.

"Toulouse Street" and "Broad Avenue" are the sections most affected by early rock ‘n’ roll. In the C of "Broad" these sounds meet Romanticism to blend seamlessly, voicing a beloved conjunction I had carried at some level since early childhood. In the second half of "Broad" I'm not only immersed in the identity of a street; I'm a little follow again in Kreole in 1959, rocking to Fats Domino 45s at the house trailer that was my first home. "Toulouse Street" remembers my days of playing at the Toulouse Theatre, an establishment closely associated with the eccentric blues and rock ‘n’ roll pianist James C. Booker. The A of the piece is my distillation of memories of James' approach to the popular Carnival song, "lko, Iko." Rock 'n' rollish elements tinge much of the rest of Streets, including "Jackson Avenue," "Magazine," "Annunciation" and "Interlude."

Here, then, is the first recording of the musical effort I've called my most gratifying, a work flooded with associations I dare allude to only obliquely.

Let these remarks be your turnstile to my spectrum within America's sultry museum-of-a-city. May every listener be prepared to brave a measure of its elegance and decrepitude, its terror and tenderness, its adolescent vitality and staggering loneliness.

David Thomas Roberts, Summer, 1988